Tuesday, 14 October 2008

Exposures - what film taught us

f/16 for a sunny day

f/8 for overcast

f/4 for a setting sun

The shutter speed will be determined by the ISO of the film. So if we were using ISO 100, then we could be using 1/100 or 1/125. If we were to use ISO 400 then 1/400 or 1/500; it's essentially a reciprocal.

Even on a digital body that can account for the exposure, knowing the equivalent for manual exposures will help on the technical side of photography.

Saturday, 20 September 2008

Constructive tutorial (3) - Palakaboy

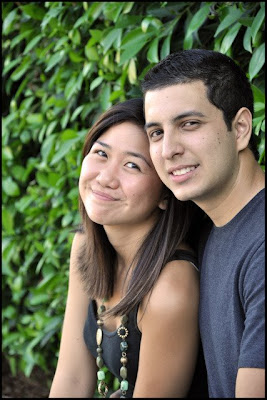

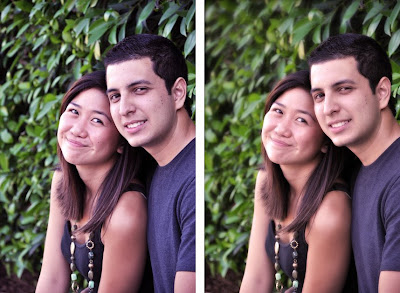

The composition is solid, as is the exposure. But what we lack here is dynamic lighting and a problematic background. The DoF is quite deep so we have leaves that are competing against the subjects, and as mentioned in my outdoor portraiture entry, green backgrounds close to subjects will act as green reflectors - we have that green cast on the midtones of the skin. Both these issues we can adjust with some knowledgeable post-processing - the issue with the lighting is harder, but we'll see what we can do. Here goes:

We can use techniques to blur out the background, but we don't want to blur out the subjects. To get around this we can duplicate the background layer and extract the subjects in a separate layer. Once extracted, this will allow us to manipulate the leaves separate to the subjects.

To alter the background, gaussian blur is needed, but a common error is to make it look very artificial by having a uniform flat blur. We can conceal the editing by duplicating the background layer again and gaussian blur the layer. Choose enough by looking at the preview and apply it. A layer mask is then added and we use the gradient tool to select where we want focus to be and have a gradually increasing blur away from the subjects to give a less static background blur.

The final part is to make the subjects look good in the light. Green casting can be removed by using coloured filters, selective colour, colour balance and curves. All four methods are shown in the video.

We can also make the subjects radiant - we duplicate the extracted layer and run a high pass filter. To know how much to run through, we guage by using the gaussian blur function - we identify how much we need just to make the skin look smooth but not too out-of-focus, and then we take this value for our high pass filter. After the high pass, we add a gaussian blur, but roughly only a third of what we applied for the high pass. In the video I used 1.5 for the high pass, and consequently 0.5 for the gaussian. We hit Ctrl+I to invert the layer and then choose Overlap as our blending style. This gives a radiant look on the subjects, and a handy technique in hand if you want to hide some skin blemishes. I chose Overlap to accentuate the effect, but we could have quite easily used Soft Light. Using the Soft Light blending style will give a more muted effect than Overlap.

The end result we have is shown on the right with the original on the left (as always, click for larger images):

The hurriedly made video below goes through the above techniques (though I may re-record it at a later date):

I hope there are some useful processing techniques to take away, and thanks again to Palakaboy for letting us learn through his work.

Monday, 15 September 2008

In from the cold

More can be found on my official website: www.edtangphotography.com

Wednesday, 10 September 2008

Constructive tutorial (2) - Alastair

"Hey Ed!

I would love it if you could give this image a bit of a critique and edit (if needs be). I'm very happy with it although not completely pleased with the tree on the right but I think overall it's a good photograph and had a particular mood to it. What do you think?"

It's a pretty landscape. This small version above doesn't quite do it justice. A larger version is available if you click on the image. What works here is a well captured sky that's filled with interest. The cloud formations as well as the distant horizon bring lots of promise to this image. It's not all good news though - we have a situation completely the opposite to the last tutorial with Thomas' image - we have too much contrast here. There is a large dynamic range between the sky and the foreground; this accounts for the dark and underexposured trees. But there's no need to despair! Underexposure is easier to correct than overexposure in post-processing, so all isn't lost. I'll talk through what we can do to rescue much of the detail in the video. The other issue we have, and Alastair has identified himself, is the composition. The trees aren't quite placed "perfectly" to be pleasing on the eye. Again we can remedy this, and I'll talk a little about some fundamentals in composition in the video.

Finally there isn't an immediately obvious focal point in this photo. The peak lies close to centre, but is marginally overexposed and blends in with the clouds; we have the dark underexposed trees in the foreground, but they don't act as leading lines into the image. I found that my eye wandered across the image. But again we can remedy this, and the other two issues mentioned:

I've used the construct of the golden mean as well as a natural frame with the dark trees and clouds. This should give more lead into the frame and not let our eyes wander far off. What we've framed is that peak and all the depth behind it. We've also reclaimed a bit of the foreground and added even more drama to an exciting sky.

Here's the video (in two parts) that talks you through my analysis and what I've done.

Once again, this is only my interpretation of how the image should be. I hope I've explained the concepts behind what I've done and if there are questions, please post them in the comments section at the end of this.

I'll finish off with a little in-camera technique. I haven't a clue how Alastair focused for this image - if it were focused at infinity at the peak, that wouldn't be unexpected. However if you're exploring great DoF whilst retaining sharpness, there is the hyperfocal method. You focus one third of the way into the frame using a small aperture, f/11-16. This is because DoF extends two thirds beyond the point of focus. This should achieve a greater DoF and sharper image than just focusing at infinity.

Many thanks to Alastair for providing us with a great image to learn from.

Tuesday, 9 September 2008

Constructive tutorial (1) - "thomasrichards"

The second issue is bigger and that's the lighting. There is a green tint caused by your surroundings (see my post on outdoor portraits here). In essence the trees act as giant green reflectors. But green tint aside, there isn't enough contrast in lighting between the model and the background; it lacks punch. So here are some pointers that you could try in post-processing:

- Increase contrast between model and background by using several techinques that included the use of layer masks with brightness increase, contrast decreases and increases, levels adjustment, altered channels, high pass filters, warming filter, and diffuse glow."

It appeared to be a popular edit and I've been inundated with requests on what I actually did. Rather than just telling you how, below is a short video that will go through all the steps I went through to obtain that end result.

The editing was done with Adobe Photoshop CS3 on an underpowered Asus Eee 901. You'll see the embarrassing "low disk space" warning during the clip. The resolution and volume also aren't impressive. However I hope it's clear enough what I've done and how you could do the same.

- a little oops. I just watched my video in completion and realised I'd forgotten to add a warming filter. The standard warming filter (86) at 11% is what I added to the edit I've posted above. This is a step missing at the end of the video. Also missing is a step I use when prepping an image for printing - sharpening it. I favour a method of duplicating the background layer and then placing a high pass filter - give it just enough so that you can faintly see the major outlines of the image under the grey - then overlay that layer over the background. If I have another chance to make a video tutorial again, I'll make sure I go through these.

Of course this is my interpretation on what I thought the image ought to look like. There may be differences in opinion, but this is photography!

Many thanks are owed to Thomas for kindly letting me use his image for this post.

Monday, 8 September 2008

More on Photojournalism (the "grab and go")

It essentially is what I call it; a bag that's ready to be taken at the very last moment for an assignment that's been given at very short notice. Let's make a list of what's in this bag:

- Number 1: I lie. It's more than one bag. Make it two or three. Organise it so that you're not carrying two of the same type of bag. A rucksack and a rolling suitcase might just do. The suitcase is most handy for flights, and the rucksack for the unknown or emergencies. In essence with breaking news, a PJ doesn't really know their sleeping plans. The main aim is to cover the event. The rucksack keeps everything compact and on the go without the need to trawl a suitcase for instance.

- Back to the contents of the bag: it should contain some basic clothes for two days, a rudimentary personal kit, a hand/bath towel, a spare pair of shoes and crisis kit.

- The personal kit should include a toothbrush, toothpaste, pack of travel tissues, hand wipes/alcohol gel, deodorant, a bar of soap, comb, hand mirror, a disposable razor and a travel sewing kit. You might decide to add a few common medications in case of illness, such as simple analgesia (paracetamol/acetaminophen), anti-histamines (in case of allergies) or a mild painkiller (ibuprofen). There's always a risk with insects when travelling abroad, so the rolling case usually carries a form of insect repellent.

- The crisis kit is really a mix of essential and excessive elements to the "grab and go". Some simple sugary snack should be included. A pack of sweets or a small jar of honey will do. This can be mixed in with warm water for a shot of energy. Likewise sachets of instant coffee/hot chocolate. Additional food can be stored in tin cans - usually 2 or 3 will do. Bottled water is a must and pack as much without weighing down the bag (~2/3L). A compact first aid kit that's been checked for the contents (often it may get used in the field and isn't replenished as an oversight); travel power adaptors (plus power cable for the phone - a laptop is a luxury in this bag [more often found in the camera bag], but if you can bring one along with a charger, then do), spare AA/AAA batteries which can be used in common appliances; torch, compact wind-up radio, handheld TV, alarm clock, notepad, writing utensils, string/rope, duct/electrical tape, bin bags, penknife (with can opener), raincoat, emergency thermal pack.

- A pack of cigarettes. Awesome item to have for trading.

- Along the way to the airport make sure to have a chance at purchasing a map for your destination. If it's a national event you're heading to, a local map should be somewhere within the "grab and go".

And then there's the camera bag...I'll save that for another time.

Sunday, 31 August 2008

Running out of juice

I made the leap into DSLRs and enjoyed making photos without needing to think about how many shots left before film had to be reloaded. What I duly forgot on one outing was "reloading" the battery in my new camera. Inevitably I lost power at the worst possible time and missed plenty of opportunities, and that was one of the more important lessons I've learnt with digital. Check power the day before you need to use your camera.

But other than checking, there are ways to reduce the likelihood of such downtime. Carrying a spare battery is one method. But make sure that that's charged too!

A more costlier method is a battery grip. It can be a practical solution to utilise two batteries whilst giving better handling in a portrait orientation. A grip shouldn't just be an additional block to add onto the camera body. Official versions usually have a thumbdial (or two) to adjust settings, and an electronic shutter release. There are third party grips available in the market that don't have thumbdials or an electronic shutter release. I'd recommend caution when using these. They give the benefit of utilising a second battery and improving handling in portrait orientation. However they are useless when in that rotation. In portrait orientation you have no control over the camera, and you therefore have to reach over to the original grip to control the thumbdials and in releasing the shutter. With this in mind, for all those who've been seeking a grip for the paltry Nikons D40, 40x and 60 - there's no point. A spare battery is better. If you're attempting the vain notion of making your camera look more professional, it really doesn't matter. It's not the camera that's important about a professional - it's how YOU use it. Bear in mind these 3 cameras were also designed small and compact - the idea of a grip is against this - and therefore Nikon never made electronics capable of accepting a grip with an electronic shutter. Third-party grips exist but with infra-red releases that don't allow auto-focus.

Moving onto other cameras in general, a grip with the right controls will provide extra juice in your camera while also increasing functionality in the portrait orientation. It can also balance the camera when heavier lenses are fitted. Some grips also have an adaptor to fit AA-sized batteries - a handy addition when you run out of power in the field and there are stores nearby. AA-sized batteries are quite common that they can be easily found.

If you're shooting a wedding, I'd recommend bringing at least a spare battery and your charger - you can then roll batteries. When you drain one battery, you simply swap it to the spare and then recharge the one that's run out. By the time you're getting close to draining the spare you ought to have another that's fully charged.

Until next time.

Saturday, 30 August 2008

Choosing a camera

#1. Assess what you want.

Putting it simply there are different cameras for different purposes. Knowing what you want will narrow down the list of potential candidates and make decisions a little bit easier.

Other than the functions of the camera, put into consideration your budget and future aspirations with your new gadget. Will you take photography seriously and need room to expand your collection of equipment? Or do you just want a camera to take around in case there might be an opportunity for snaps?

#2. Trying the cameras.

Bring a memory card (if you have one) to a camera store to test cameras. It will let you record and take home test images to review later.

#3. How the camera feels in YOUR hands (IMPORTANT!).

There's a different camera for each one of us. How it feels physically is a key distinguishing feature. If the camera feels a little awkward or doesn't feel good at all, it really isn't going to persuade you to take more images.

Things to consider when you're handling a camera is the weight, size, grip, how easy is it to compose a picture on the screen or through the viewfinder, and build quality.

For this reason I'd recommend going to a camera store and play with the cameras before making a decision. You can always make a purchase online after careful consideration.

#4. Dispelling myths.

There are two long-standing myths out there - more megapixels doesn't mean a better camera, and a better camera doesn't mean better pictures. Confused? Here's why.

Digital cameras record images through a sensor. This sensor only has a finite amount of surface area. It is on this area that information from light is converted into pixels. So if you have a large number of pixels then they're more likely to be cramped on the sensor. In low light conditions the pixels will 'fight' one another for light and the result is a grainy image (digital noise). Then there are different sized sensors - in digital SLRs (DSLR) a common size is the APS-C sized sensor which is larger than a sensor in a compact camera. This means that each pixel on a DSLR sensor is bigger than in a compact for the same given number of megapixels. The underlying message is don't judge cameras by megapixels.

The second myth is a better camera doesn't mean better pictures - it's the photographer that chooses the subject for the photo and takes the picture. The camera merely facilitates. The camera is often only as good as the person behind it.

Now having said that - how can we actually compare cameras then? Well how they feel in our hands certainly will play an important part, but image quality is what we want and how we judge the ability of a camera by. Test shots taken from testing a camera in store is useful to help determine this, but reading reviews by trusted websites and magazines may also be of use. Having said this, do be aware of bias and amateur reviewers who don't necessarily know what they are talking about.

Choosing a camera isn't easy. It gets easier the more advanced a photographer you are when understanding builds up and you know what to demand from your equipment.

I personally use the Nikon DSLR range and their system of lenses and flashguns. That doesn't mean they are the best (in fact I dislike some of their products) - it just is the brand that provided the camera that felt right for me and gave exactly what I demanded and still demand. On occasions I use Canon and Olympus equipment to keep myself familiarised with what's on offer from the other manufacturers.

From a more advanced perspective, if you wish to take photography further then you should be considering the following:

- a DSLR (it will allow more room for future expansion than a superzoom or compact camera)

- good lenses that fit your purpose

- adding additional external flashguns

- accessories and peripherals (bags, straps, cleaning equipment)

But this doesn't rule out buying a compact or superzoom camera - remember that the camera is only as good as the person behind it.

All the best.

Tuesday, 19 August 2008

Outdoor portraiture - lighting 101

The topic today is the ability to control outdoor lighting. "Control sunlight?" you might ask, "Surely that isn't possible?" Let me assure you that it can be done. Obviously we can't move the sun, but we can do other things to alter the effect of light. Here's a run through some of my most used outdoor lighting techniques:

1) Gobos (and shelter). Tip #1: Run for cover.

If you haven't encountered gobos before, they're objects that alter light by blocking, coloring, or diffusing some portion of the beam before it reaches the lens. One of the better gobos to interact natural light with outdoors will be tree cover. Let's review why this could be better for your pictures; by having cover over your (photogenic) subject you can control the direction that light shines on your subject. What this does not mean is to stand your subject in complete shade! Otherwise you end up eliminating natural light and needing the support of artifical light (fill flash - more on this later). You'll also create a cove of green coloured light reflectors which casts a green glow to your images. Again more on this later.

What you aim for is light shining on your subject but from a direction dictated by the surroundings. In addition to direction control, light can also be mildly diffused. It can naturally provide that soft light that portraiture is often associated with. My artistic skills are pushed to the maximum with the diagram below that illustrates lighting control by cover.

Note that here I've illustrated the subject not entirely covered by the trees (see the bold above). We don't want the sunlight to be completely blocked from the subject.

And there we have it - a way of controlling the direction of sunlight! It's particularly useful in the dreaded midday sun. You can replace trees with any form of shelter over the head (gazebo, bus shelter...etc) hence tip #1: run for cover. Cover will give you much more control over light.

2) Fill flash and strobes.

A lot is covered in resources over how to use fill flash. I'll not cover that part except mention that it is useful and shouldn't be neglected. Deliberately underexpose the strobe if you're unsure of how much power is needed to prevent a washout. An added tip that isn't often mentioned is the combination of fill flash with a high shutter speed to cause a pleasant portrait with a dark background. I have no releasable examples of this, so you'll have to take my word...

Other fun things can be done with strobes outdoors beyond fill flashing. If your model has dark hair that blends into the background, why not try a strobe behind your model with a snoot or grid (both increase the intensity of a strobe light by concentrating it into a narrower beam - make sure you combine this by setting your strobe to a tele setting) and have it as a hairlight? This will create some dramatic contrast between the background and your subject.

If you don't have a strobe for a hairlight, then fear not. You can try an elementary form of rim lighting. Controlling the natural light with cover, you can use it as the hairlight, and then the on-board flash as fill.

Saving some material for the future we could apply crosslighting with one strobe. If you are able to control the direction of sunlight with cover, then a well-placed strobe facing directly into that sunlight with the subject in between the two sources can create this effect. It can be very dramatic. Again no releasable examples...

And no doubt you can do a websearch for other multiple lighting techniques in Y or T configurations, but they all work on the same priniciple - you need to be able to control lighting direction. If you haven't got the message by now, read and repeat tip#1 several times.

3) Reflectors (h)and towels.

Reflectors can be fabulous lifesavers. They're simple and a great way to redirect light. My most common uses are either to bounce strobe light (and diffuse it in the process), to place it on the lap of my subjects, or drop it in front of their feet. You may ask why the latter two? Well think of the outdoor environment as your studio. The floor may well be covered with nature's carpet - grass. And when light bounces off grass, it gives off green light. And green light isn't flattering unless you wish your subjects to look like Shrek. The placement of the reflector simply removes the green haze in some portraits and reduces difficult post-processing later.

And this goes back to my point earlier regarding tree cover. Complete shade under trees will essentially place your subject in a natural studio with greenish walls. Not particularly good for skin tones, if you ask me...

Now you might wonder why tree cover with light shining onto the subject won't cause the green cast. Well it does. But if your light hits the subject 1st on the face (as in portraiture) you don't have reflection from the green stuff. And so you don't get the casting on the face. For three-quarter or full length portraits, there may be a slight glow to the rest of the body but barely noticeable. If not, you'd be using...reflectors!

A wonderful alternative to a reflector is a white towel. I often have a white hand towel in my bag that serves this purpose (or to wipe sweat on those warm summer days). Small, compact, cheap and multipurpose; you can't ask more than that!

4) Good direction.

This follows on from an earlier post on directing models. Knowing how to move them in relation to light is important. There are many ways of doing this, but two things to remember are the following:

Tip#2 It's not a good idea to stand them facing directly into the sun as they are likely to squint. Exceptions: sunglasses, turning the head of your subject, or your subject isn't human...

Tip#3 Look where the shadows are. This also means your shadow!

Hopefully this brings some useful aids to outdoor portraiture. As always, comments are most certainly welcome, and I wish you happy snapping in the meantime.

Wednesday, 23 July 2008

Sincere apologies

Wednesday, 25 June 2008

Brief intro into Photojournalism

The joy of being involved in a part-time journalism/photojournalism role is that the burden of deadlines isn't always looming. I've been exposed to this field for the last two years and it has been a good experience, assisting my self-development in photography.

However a distinction should be made between being a photographer and a photojournalist. The difference is subtle, but distinguishable. Let's use a parallel in terms of grammar. A photographer looks for shapes, textures, colour, the subject – essentially the capturing of nouns. The photojournalist looks to capture actions, a story – verbs. And this difference between nouns and verbs is that subtle feature between the two.

Capturing verbs isn't easy; some moments are spontaneous and could be missed if under- or unprepared. This of course adds to the pressure on delivering images that the editors can use for their stories. So what can be done to increase the chance of capturing these brief moments and also a narrative? I guess it comes back to one of my basic philosophies (and it was heavily repeated in the past post on Weddings): preparation.

Preparation here has to be meticulous if the event is of high significance. Let's take a protest as an example. The location has to be sourced and if there's going to be a march, then the planned route should be researched and then scouted for potentially good viewpoints. As with outdoor events, the weather will play a factor, and so the forecast should be looked up and that may determine what gear could be in your kit bag. Other things to consider is police presence. Major protests will of course have police presence, and if you're aiming to cover the events for publication then seeking a press pass will assist greatly. On early arrival for the event, make your presence known to the police and see if they have any pointers on potential spots for trouble – this could provide further opportunities for images.

The last part is liasing with the writer of the story (unless it happens to be yourself as well). If there is a particular take on the story, this may influence what types of images the editors might want to fit in with the writing. However this doesn't mean that the photographs have to all fit this particular angle. There may be an image that you capture that opens an entirely new direction for the article.

Once the images are captured, they then need a short descriptive line, known as a cutline. This essentially can be structured as follows:

[noun] [verb] [direct object] during [event] at [venue] in [city/ geographical location] on [day of the week], [date], [month], [year]. Reason for why or how this happened.

The images once captioned are either fed through an FTP, emailed or dropped into the office. Very little editing is ever done to the images (for the fear of misrepresention). The turn round time here varies from publication to publication from hours to days.

And there we have a glimpse into photojournalism.

Monday, 16 June 2008

The tilted perspective

Here is the same image again from a tilted perspective.

Now those leading lines are all in a different configuration. The two bannisters still pull the eye towards the distance, but now we have the asymmetry that also is pulling on the eye. The brown brickwork and the glass roof make the top half a very contrasting part of the frame. I used this to create a powerful line because of this contrast - the eye is more taken by the glass roof which leads to the distance. The bottom left of the frame is aligned with the bannister to create a second line. To top it off the degree of tilt was determined by aligning the transistion at the top between the glass and the brickwork so that it formed a vertical line downwards. What this does is create an impression that the market hall could be longer than it is in real life because of the exaggerated lines. Now one example isn't enough, so here's another:

So the theme I hope I've established is that the tilt isn't something that can be haphazardly used. You need at least 2 leading lines, if not more, for this perspective to work strongly. It's preferable to have the centre of the frame as the point where these lines converge, though it doesn't have to be the case from time to time. Again I'll illustrate this.

Here is an image of St Pancras Railway Station. The leading lines from the bannister and roof are similar to the one above from Covent Garden but the tilt here is noticeably less and also to the other direction. You might be asking why - and that's down to the odd leading line of the escalator. This doesn't lead to the centre of the frame, but to the bottom third. What this can add is another line of interest to the image.

We've now identified what needs to be there for tilting - leading lines to a focal point. But how can we tell when is a good opportunity to tilt, and then how much to tilt it by?

The answer is simple - experience and interest. We view the world from a horizontal perspective; as photographers we seek different perspectives - hence the suggestions of lying low or climbing high for that difference from eye level. What we sometimes neglect is that at eye level we can also tilt for that difference. Composition doesn't have to follow the basic rule of thirds as we're manipulating converging lines instead. And it's the convergence that tells us the tilt. Strongly convergent lines like the market hall can give greater scope for tilting, whilst gentler lines as in the railway station accommodate for less.

In the end it comes down to experimentation. Often a little trial and error to find the right angle is needed, and to find that different perspective that we don't often see every day. Good luck!

Thursday, 12 June 2008

Tripods

The tripod is a fundamental tool in the photographer's armoury. Used wisely, it can achieve fantastic images, and used inappropriately, it becomes restrictive. Let's go through the basics to a tripod, and then have a review over the tripod that I use - the Manfrotto 055xProB.

A tripod can cost next to little and also a fortune, and for most part, it's hard to justify spending a lot of money on a tripod unless you take it very seriously. Regardless of price though, one fundamental criteria exists:

How sturdy is this tripod?

The amount of stability you need will depend on the weight of the camera that you plan to pair the tripod with, so the heavier your gear, the more sturdy your tripod should be.

Secondary things to look out for are release plates, leg mechanisms, material and weight. Let's go through each in turn.

A release plate is a detachable attachment on the head of the tripod that allow your camera to be removed from the tripod without the need to screw or unscrew it. This is very handy if you plan to work both handheld and with a tripod.

Leg mechanisms - twist systems or thumb locks are the two common mechanisms found. Twist systems are faster to operate, but generally more expensive because of the extra engineering involved in the manufacturing process.

Materials and weight - both are inherently linked, and lightweight materials such as carbon fibre will cost more, but being a rigid material, will retain the sturdiness. Benefits of having a lighter tripod will be obvious when needing to carry one for a long time. Slightly heavier materials such as magnesium and aluminium are used in quality tripods to give a good compromise on weight, rigidity and cost. The heavier weight may mean more effort needed on carrying such a tripod on hikes, but will be less an issue if it's going to stay in a studio, or will be used on occasions.

The more expensive tripods come as legs only, and a separate tripod head has to be purchased. Although this adds more to the cost, it actually offers more flexibility. There are different styles of tripod heads that will be suited better to different photography styles. I'll list 3 major types -

The three-way head: the classical head and offers an all-round performance with the ability to rotate, tilt side-to-side and up-and-down.

The ball head: essentially a ball and socket mechanism that allows for fast adjustments of the camera, and therefore a very useful head for action photography, especially panning.

The panning head: This is a head that has fine tuned rotatory action and calibration for taking panoramic pictures. The handle on these heads tend to be longer than a three-way head.

Now onto some basic uses of tripods:

1) Night time photography - a tripod will hold the camera stationary and will allow for long exposure times, such as the light trails from traffic. Now with this example there was a technical difficulty with getting an exposure time so that trails were visible, but the advertising boards in the background wouldn't be overexposured. A simple trick was used to prevent this - a piece of black card was held after a second of exposure time across the top of the lens so that the boards wouldn't be overexposed. The traffic trails were captured over 4 seconds.

2) Landscapes - a tripod will slow down working with a camera, but with landscapes this can give time to settle down, think of composition and alignment of horizons before an image is taken. With deep depth of field, a small aperture is used, such as f22. This generally means a longer exposure time, and the tripod will be able to hold the camera steady.

3) Studio work - a tripod can be used to keep the camera stationary and fixed, so in a studio photoshoot where multiple takes may be required, this offers consistency. Of special importance is macro work and focus stacking (the overlaying of images with different depth of field control to produce one image with immense depth of field). Sadly I have no examples of this to hand.

Regarding my tripods of choice, the Manfrotto 055xProB is used in my macro and night photography because of the stability it offers. I pair it up with a separate head - the 804RC, which is a low end three-way head that does a very good job. However it is cumbersome to carry for long periods of time, and so I have a more portable Manfrotto MN785B Modo Maxi that supports upto 1kg. This tripod is less stable, so it isn't as useful for night and macro photography. I use it more often in landscape photography where a light tripod is needed for hiking.

I guess the difference between the casual and the seasoned photographer when using a tripod is the knowing when to use one, which means the planning ahead on bringing one. The appropriate use of a tripod - regardless of price point - will generally yield better results by eliminating camera shake.

And there we have a basic run through tripods, and a little on when to use them.

A week on...

Thank you for reading my ramblings this week. If there are specific questions you want answered, topics that I've not yet covered, suggestions for improvement, or anything in general - please leave a comment.

Regards,

Ed

Model releases

I'll speak from the UK perspective, as respective laws in different countries vary. On my travels I adopt the "I'll get a model release form signed if in doubt" approach.

In the UK it's not a legal requirement to have signed release forms. For example if you are hired to take images for a wedding, modelling portfolio or for a portraiture session, it's advisable to have the terms agreed to prior to payment. The photographs belong to the photographer with the UK law, who has the right to do anything, from publishing them without recompense for the model.

Street photography and candids are again images that belong to the photographer. However it is courteous behaviour to either seek permission to take an image, or to take the image then let the subject know what you've taken, and if they object. Private property is treated the same as a person, and consent ought to be sought prior to photography.

For photojournalism, this same approach applies - if you're capturing people at an event, let's say something sporting, or a speech, there will be prior agreement for your presence to photograph from the publication you're working for or if freelancing, by calling up the organisers in advance. But those photos from the event are yours unless the organisers impose restrictive conditions for photography, such as all images are restricted to being published only in the publication you work under, or have agreed to work for and cannot be sold for profit.

Therefore the model release form might appear to be rather limited in scope (and photographers are less likely to be sued and are sadly now more likely to be stopped by police in public - a topic that will deserve a post of its own). However I should cite areas where its use could be useful.

If you're taking images of children, seek prior permission with the parent(s) or guardian and have a model release formed signed. And if images are going to be submitted for stock photography, many sites now require written release documentation for their own protection.

As mentioned, laws are different from country to country, and so I use release forms whenever in doubt. The one I now use is from Getty Images. You can find a brief overview on how the release form works as well as collection of release forms in different languages from the link below.

http://contributors.gettyimages.com/article.asp?article_id=991

Wednesday, 11 June 2008

Amendment on Renting equipment

Tuesday, 10 June 2008

What less common things can you find in my bag?

1: White bounce cards - these can be made of card or thick paper. I use 3 x 5" index cards. They are very useful to diffuse light by bouncing when there are high ceilings, or a non-neutral colour on the walls. They double up as a means of calibrating custom white balance.

2: White hand towel - two purposes (like most items in this list...): one is as a towel - to wipe off sweat during the pressures of an assignment, secondly it can be used as a reflector outdoors, especially with grass. Grass reflects a horrid green glow, and simply laying the white towel in front of your subject can reduce this glow and also lift some shadow.

3: Step-ladder - useful for group events, such as weddings or parties. Combined with a wide angle lens this gives a higher perspective. It can double up in portraiture work where a high perspective can be taken; it can be very flattering for a model to look upwards towards a camera as it can hide the body and pull in more of the jaw line.

4: White umbrellas - have a few white umbrellas and if it rains for yourself and your subjects. The white material doubles up as reflectors and lifts shadows. In sunnier conditions they can be used as reflectors in their own right, and indoors they can be opened up and used as a surface to bounce light from. For the more meticulous, having all umbrellas the same also makes for a more professional image.

5: Tape - useful in studio work to mark out positions for lighting, or where models can position themselves.

Sunday, 8 June 2008

Renting equipment

Let's assume I cover three sporting events a year, and for those I need a fast telephoto lens, say a 300mm f/2.8. A rounded UK cost of a Nikkor version of this lens is £3000 (US $5800). So for each time I use the lens it will cost £1000 (US $1960). This is a heavy price to pay for an occasional use lens, so instead of tying up capital that could be used for other things, rental becomes an option. Renting the 300mm f/2.8 is approximately £50 per day (US $98) and £200 per week (US $392).

Therefore rental of this lens for 3 days of sporting events will be £150 (US $294). This is far less than the £3000 (US $5800) that would have been paid if the lens had been bought.

Other than the lower price there are also other factors to consider. A 300mm f/2.8 isn't cheap to insure - rented equipment will be covered for most incidents under your rental. The lenses will also be regularly serviced to make sure they are in top condition.

A further point would be on travels - on location you might not be able to carry such a large lens onto aircraft, or it would be logistically impractical. Rental once you're at location is an easy way to ensure no equipment gets damaged in transit, and that you won't need to pay extra to carry overweight handluggage (lenses and other camera equipment should never be checked in so keep it with you).

However it isn't all that rosy - it is common that a substantial deposit is left or for credit card details to be retained so that the rental company has a guarantee that the lens gets returned, and there are usually fines for late returns.

And there we have it. That's a brief overview on some reasons why professionals consider renting equipment.

EDIT - please see the amendment dated 11 June 2008.

Workflow - from camera to working image

The underlying principle is very simple: be able to get an image off the camera with the correct colour - process it if necessary (but not for photojournalism) - get the image out, get paid and move onto the next assignment/project.

So let's take each step in turn. First we have to get the image off the camera. A fast card reader and also a set of fast memory cards will be very useful. I'm not terribly brand loyal when it comes to cards, and have a collection of high speed cards from Lexar and Sandisk. I find it best to transfer all files to a folder named after the assignment on my desktop as my working folder.

This is the beginning of getting the images out. The next part is making sure I know where my images will be going - if it's for print, then I need to select the paper, the printer and the size I will be printing prior to any processing. Why? Because I can adjust my colourspace to accommodate for the final results. Colour management is very important in the workflow process and shouldn't be neglected. I select the correct profiles for the work and begin processing. This may simply be resizing the image to some more advanced work. But here's the trick to reduce workflow - get the image right in-camera. This really does cut down the amount of work needed, and images can roll off as straight RAW to TIFF conversions with a watermark action in Photoshop if need be.

Now I've alluded that I don't process for photojournalism - and this is a strict code I adhere to. Yes, digital photography should embrace the editing element, after all, that's one reason why it's become so popular over film - but for journalism you simply cannot take the risk of publishing an image that may have been falsified. Therefore publications and editors I've worked for would like the images as shot. This again means that getting the right image in-camera is vital.

Processing should deserve a few posts with examples, so I won't go into detail suffice to say that this is usually where most time is lost in workflow. Therefore I do the following before each assignment:

-clean the sensor and test for dust spots with the aperture closed as far as it goes over a brightly lit piece of white paper

-make sure I have a grey/white card with me if I'm covering indoor events so I can customise a WB. Outdoors I will use auto WB as lighting will change, but indoors, lighting tends to stay static.

If all images have a dust spot or the wrong white balance (WB), then every image needs to be recovered. And this is a pain for workflow. Imagine that each image takes an extra 5 minutes to correct - that's an hour lost for every 12 images. That one hour could be used to go and cover another assignment.

And that's really it from a simple summary. I'll make sure to go into more specific parts of this whole workflow process which one post can't possibly do justice. Again, if any questions arise, please leave a comment.

Friday, 6 June 2008

Are you lost? Where's that sense of direction?

1. Plan

Before a camera is even picked up at a photoshoot, plan. Plan, plan, plan! At the very beginning there is so much to consider and think about. A plan will help structure your photography so that you know what you are trying to achieve. Having that goal will make your life easier as you have a sense of direction - and being the director behind the camera, it would be mortifying if the director had no direction! The plan will be based on what the photoshoot is for. Is it for a client or for yourself? That will dictate the brief. If it's for a client, listen to what they want, and then plan around that. For example, if it's fashion then you have to consider what's being worn and what surroundings will fit in, and then consider portrait-orientated ideas in full length or 3/4 length. It's less likely for the camera to be in landscape-orientation for fashion. Other things to think of here would be what equipment to bring to achieve the goals you want, if you're shooting outdoors - what time of day would be best? This is important for lighting. And if it's indoors, what sources of light are you going to use? Window light, artifical light? Planning ahead will give you a sense of direction.

2. Build a rapport

This is where most photographers come unstuck. There's either no rapport or the person(s) you're taking images of are familiar to you that this is forgotten. You need to interact. Talking is a good way. Find out their interests - talk about what makes them feel comfortable. It's wise to read the newspaper or headlines on the internet on the morning of a job so you have topics to discuss. And once you start talking, keep talking. Even during the shoot, carry on your conversation with perhaps the odd interruption to tell them to lift their head or look a certain way. You might be asking me: "Why do all this?" Simple. A relaxed person in front of the camera makes for more genuine expressions and the time appears to fly faster. It can also be more engaging. Look at it from another way; which photographer would make you uneasy - someone who was fumbling around camera settings or unsure of how the lighting looked - or a talkative person who knew what they were doing? So try and relax your subject. I've heard of photographers who've used music to settle their models in studios. Anything goes - but aim to relax.

3. Avoid static postures

Once you have a working relationship, you need to be able to advise (or even control!) the person in front of the camera to get the right "look". I avoid the word "pose" - all will be explained shortly. Seasoned models will do it better than ordinary people, so let's assume we're dealing with ordinary people.

The likelihood if you ask someone to stand and "pose" is that they stand still and look straight into the lens, have a hand on their hip and pout, or have their hands in their pockets. All very well, but they're cliche and not dynamic. In the business this is what we call "static". There are times were a static posture will work, but on the whole, they lack a bit of magic.

4. Be dynamic

This is the opposite of static. Essentially the term "dynamic" is tagged to postures that are mid-movement. Here's an illustration on the left (click for larger). This was a charity "fashion show" and the models were all ordinary people who were doing it for fun. Too many were like the girl on the left. Walking and looking at where their feet were next going to land. As you can imagine, that doesn't make for pretty pictures. Being close to one side of the runway, I got interacting. Now I can't remember what I said to the pretty girl in the pink satin, but she took notice, strode towards me, looked into my lens and smiled. So the way she appears in this image could be called dynamic as she is visibly mid-stride, and you can picture her swinging her arms with her left foot moving forward.

Now in a more likely situation that you find that you need to get your subject dynamic, you can use this simple technique. Get them to stand one shoulder slightly forward, and turn their head and look towards your lens. Simple, yet dynamic.

5. Know how to flatter with the camera

Directing is all about making your subject look good. This means you should know your body and face types. There are certain ways to make people look better. With a never-ending list, here are some starting points to think about.

-Let's take the above idea of shoulder forward for dynamism. It will also make the body look slimmer, and is useful with subjects of heavy build.

-If you're taking an image with more than one person, and one is significantly shorter, get him/her to stand one step closer to your lens than the others. By simple perspective (aka compression) you will be able to iron out a little of the imbalance.

-Don't take portraits from a low viewpoint (unless for a specific creative purpose). You will capture the openings of the nostrils, which aren't flattering.

-If a person has a large nose, then avoid profile photos...as I've said, this list could go on. Maybe it'll be a topic for the future.

Hopefully with these 5 basic pointers, you've got a little more direction on how to manage people on a photoshoot. But to fully appreciate good direction, why not let yourself be the subject? Let someone else be behind the camera and take the other perspective. It can open up ideas on how you could communicate ideas across to your subjects in the future.

Until next time.

Thursday, 5 June 2008

Flash work - part 2: off-camera flash

Okay, I'm writing this out-of-sequence. This will be the second part in a series on how to use flash more effectively in your photography. We'll be looking at off-camera flash. Why is off-camera flash "better" than being on-camera? The answer will become apparent here.

Okay, I'm writing this out-of-sequence. This will be the second part in a series on how to use flash more effectively in your photography. We'll be looking at off-camera flash. Why is off-camera flash "better" than being on-camera? The answer will become apparent here.I use a Nikon system, primarily because of the Creative Lighting System (CLS) that they offer. Being able to trigger flashguns wirelessly off-camera is a valuable tool. The alternative to using a wireless system is through a sync cable, which is what I've done here for this tutorial. I've also included the use of one of my more commonly used flash brackets - the Custom Brackets CB Mini-RC (illustrated on the left). I'll talk a little more about this bit of kit later on.

Before we begin off-camera flash work, let's quickly review four on-camera methods as our reference points.

All images were taken handheld with a D200 with a Nikon Speedlight, Auto white balance, 1/60, f/5.6, iTTL mode, 0 comp, with Auto FP High Speed Sync on.

1. Direct flash. Pointing the flash at the subject is the most simple way that flash can be used.

As you can see there is a harsh shadow floating behind the cruet. The flash was sitting directly on the flash hotshoe, and therefore the shadow is cast towards the far right once the camera is turned to a portrait orientation.

2. Bounce at 45 degrees. The flashgun head is tilted at an angle of 45 degrees from the plane of the lens, and so light is not pointed at the subject.

This time you can see that the shadow is a little less harsh, and light is visible in the top left of the frame. Again this is because of the flashgun sitting directly on the top of the hotshoe on the camera. We'll try one more bounce, but to get rid of that uneven light distribution, I'll be using a rubber band a white index card.

3. Bounce at 60 degrees and a classic index bounce card.

There's a difference here. The card was placed on the top of the flash head, so that when in portrait orientation, it will push light back towards the right. And we can see evidence of that here. The balance of the light is still not perfect, but where the light is falling on the white background is more to the right and away from the top left corner than in the previous example. The light is also more evenly pushed and the image is brighter. And we've got a soft shadow...

4. Direct flash and Stofen Omnibounce.

The Omnibounce is a popular diffuser amongst photojournalists because it's compact, and is effective. It is recommended that you bounce using the Omnibounce, but here I've decided to use it direct so you can compare it with the direct flash (smaller pic below as a reminder), you can see that the shadow is softer with the diffuser. The image is also brighter as light is being spread out more.

Now that we have our references, let's see what I can conjure up with the flash on a sync cord.

5. Off-camera: Flashgun to left of camera, lens height.

There's instantly a dramatic change in lighting. The flash is highlighting specific areas of the cruet that adds dynamism to the image. The shadow from the cruet gives us a clue that the flash is indeed on the left of the camera.

6. Off-camera: Flashgun to below camera right.

The last image was taken on the left at the height of the lens. I've now swapped the flash over to the right and instead on being the same height as the lens, it's now below.

So what are the differences? Well the cork stops are no longer highlighted by the flash and the shadow is harsher.

Let's try the same from above the lens height.

7. Off-camera: Flashgun to above camera right.

The cork stops are now well lit. Because the flash is aimed down, the light on the surface is more intense than the flash pointed up, as in example 6.

8. Off-camera: Flashgun directly below camera.

Rather than a flash on camera left or right, how about directly below? There's no point in directly above - that's where the hotshoe sits.

Because the flash is below and pointed slightly up and direct, there is no light cast on the surface (and therefore no shadow!) Instead it intensely lights the front of the cruet.

9. Off-camera: Flashgun front right camera.

One of my more favourite approaches though is to move the flash into an opposite direction to the camera. This illustrates a flashlight to the far right and in front of the camera. The shadow again gives us the clue that the light is indeed coming from that direction.

10. Off-camera: CB Mini-RC, direct flash.

The final example is with one of my off-camera brackets: the CB mini-RC. It's fantastic for portrait-orientated flash photography as it pushes the flashgun back above the lens, rather than being on one side if it were on the hotshoe.

With direct flash the shadow is now placed behind the cruet, rather than to one side.

This illustrates some common off-camera flash configurations, but when should a certain technique be used? That's a tricky question as it depends on your subject, what you want to highlight, and how your ambient light is. I'd neglect ambient light for the time being, and would rather discuss subject and highlights.

Let's take the cruet as our subject. If I wanted to highlight the logo printed on the front, then a standard direct flash wouldn't be useful as it will bring reflections. So what are the options? We can backlight as in 9, or have a very intense light from a direct flash below the camera. So these would be the options I'd limit myself to in order to highlight the logo.

Another example - we would like a soft shadow. That leaves us with bouncing, direct flash with off-camera bracket, the omnibounce or a direct flash below camera.

So if we think of a portrait, rather than the cruet, if we wanted a soft shadow, we can directly pinch ideas just mentioned. If we wanted to highlight the hair, then we can imagine that we're lighting the cruet's corks. So we could be looking for the flash to be placed higher and to one side, for instance.

And this is how I approach off-camera lighting.

Wednesday, 4 June 2008

Planning: Wedding Photography

Equipment:

It is a must that you're sure to have enough memory cards to last the day; typically 5 to 10 2-4GB cards should be enough. Make sure you have a filing system for your cards so you know which ones have been used and which haven't. I place my cards in a card wallet face up if they are empty and reformatted. Once finished I place them face down so I know it's been used.

Charge all your batteries and have a spare. Bring your charger with you and once you have a dead battery, go charge the it whilst you're shooting with your spare.

Tip #2: Do clean your sensor and lenses beforehand. Elimating dust spots with the clone tool on all your photos will increase your post-processing workflow immensely - so make sure you're dust-free to make life easier.

Pack your lenses. A short telephoto, macro lens, normal zoom and an ultra-wide/fisheye. I'll go through ideas on these in a moment.

Lighting - a flashgun or two. If you have videoheads or a ring flash, take those too. A reflector will be handy. If you have white umbrellas bring those too. They can double up as a photographic aid or rain protection.

Tip #3: Pack your day bag. Keep it small. Carry 2 lenses inside at most and wear your camera out. Keep a bottle of water with you. The rest we'll leave to your most important sidekick...

Tip #4: Get yourself a female assistant (explanation coming up, and I'm not being sexist) - she'll be able to go and check that the bride is decent to avoid any embarrassing situations in the build-up to the wedding. She will be your best friend for the whole day. Why? Because she makes the biggest difference. She's able to help he'll be able to go and check that the bride is decent to avoid any embarrassing situations. She can also help with organising people in group shots, hold a reflector, carry any remaining lenses, memory cards and tripod (if you planned to use one - it should be left in the car if you don't plan to use it, but there for a last minute change of heart).

Tip #5: Finally the magic things that amateurs forget/don't think of. Bring a step ladder with you and leave it in your car boot. This will be useful for group photos or to get a higher perspective with a wide lens. A camera cleaning kit in case of emergencies, such as confetti stuck to the lens... and spare shirts, because everyone sweats. And did I tell you it's hard work?

The plan:

If it is possible, do go and take some prep shots at a rehearsal. The mini-guide here is for inspiration. You don't have to follow it, but you will get an impression that I am trying to chart a narrative, which is the key to a great wedding album.

1: preparation details; follow the preparations and not the bride. She will appreciate the space and the images you capture she will likely not see during the day. Things to take are macro shots of the rings, photos of her shoes, the cake being decorated or the flowers being arranged...there are much much more. End the final part of this section with the bride. Get your assistant to check if she is suitable for a few photos whilst she is getting ready. Avoid the bulk of the make up session - just go and shoot when she's putting the lipstick and/or mascara on. Again this is to give the bride space. Have your assistant standing by to let you know when you should be there.

2: Bride's arrival: leave around 15 minutes earlier than the bride so you have time to set up. Leave more time if you think your inexperience will mean that you need more time to prepare and recompose yourself. Take photos of the groom's party whilst you're waiting and loiter around where the bridal car will arrive so you can capture her stepping out the car. Take a burst of 4-5 images and now run down the path towards the church door (assuming it's a church wedding). As soon as you get there, switch to a tele and capture a few shots of the bride walking to the church. Quickly get inside and get yourself up with a wide angle lens.

3: Church: bump up the ISO, and switch to manual control if confident, or aperture priority if not. Get near the choir at the front as that yields good angles most the time. If not, a clear view of the bride is a must. Things to look out here - get the exchange of rings, facial expressions in the congregation, the signing of the register (in the UK it's illegal to photograph this document so make sure when you do, make it plainly obvious that you are shooting below the level of the document and focus your camera on the hand and the pen). Finally avoid the vicar! Some will object to photography, but if you don't give them the chance to prevent you, all the better for you and the couple.

4: Post-Church ceremony: outdoor photos. Do not forget to lower your ISO! Too many rookies make this mistake. A fisheye or ultra-wide is effective here for group photos with interesting perspectives. Don't worry about distortion of the people on the edges - it all adds to the effect. Use your step ladder for a higher perspective. Keep things natural here, and avoid directing people around. Orchestrate them only if needed. Your assistant can help with a reflector or looking out for your next interesting group to photograph.

5: Reception: Let things flow. Capture candids here. Your venue will suit this best. Shoot the bride and groom first then the groups afterwards; lighting later on will gradually become unfavourable. Get your banked photos of the couple ASAP.

Tip #6: Avoid alcohol and keep to water and fruit juice. Unsteady hands will not help, and the alcohol may worsen the pressure of photography - it's likely that you are shooting for 10-14 hours on the trot. Flash will be necessary by the end of the reception. Check what the ceiling is made of befor bouncing - if it's not neutral coloured it can cast glows, such as orange from wood. Expose for highlights as shadows can be saved more easily.

6: The speeches - be prepared for the obvious things such as catching the groom winking to his best man, or photos of the parents and their reactions.

7: After the wedding: organise your photos so that they tell as story. A narrative makes the album that more special because it feels personalised and not just a collection of photos of the day.

Tip #7: Have fun.

This might be information overload, and I could still keep going on. Everyone has a different style of photography, and this is only one method, but one that is planned and prepared.

Tip #8: You should never cover a wedding unprepared.

Until next time, and if you have any questions, do post your queries.

The first entry...

Very briefly, I'm a part-time photojournalist, freelancing for small publications. I do a little event work every now and then.

Now the internet is full of blogs and sites that go through the basics of photography. I'll try to be a little different. As well as some basics, I will be sharing some more advanced aspects of photography.

Comments, questions, feedback are all welcome. So let's begin this journey into photography.